The record-breaking success of "Nezha 2" on the global stage underscores a century-old cultural relay, rooted in the visionary artistry of Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University’s pioneers.

As "Nezha 2" storms global box offices, redefining animated storytelling with its rebellious child protagonist, few realize its lineage traces back to a mid-20th-century artistic revolution. Behind this modern phenomenon lies the enduring legacy of Zhang Guangyu and Zhang Ding—masters of the Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University (AADTHU)—who fused folk art with avant-garde aesthetics to birth classics like Havoc in Heaven (1961) and Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979).

From the celluloid reels of Shanghai Animation Film Studio to the monumental murals of Beijing Capital International Airport, from Cannes’ first Chinese animated feature to today’s globalized Chinese animation, AADTHU has anchored China’s animation renaissance. Here, we revisit how its pioneers transformed ink and folklore into silver-screen immortality.

PART.01

Roots and Soul: The Rise of Chinese Animation

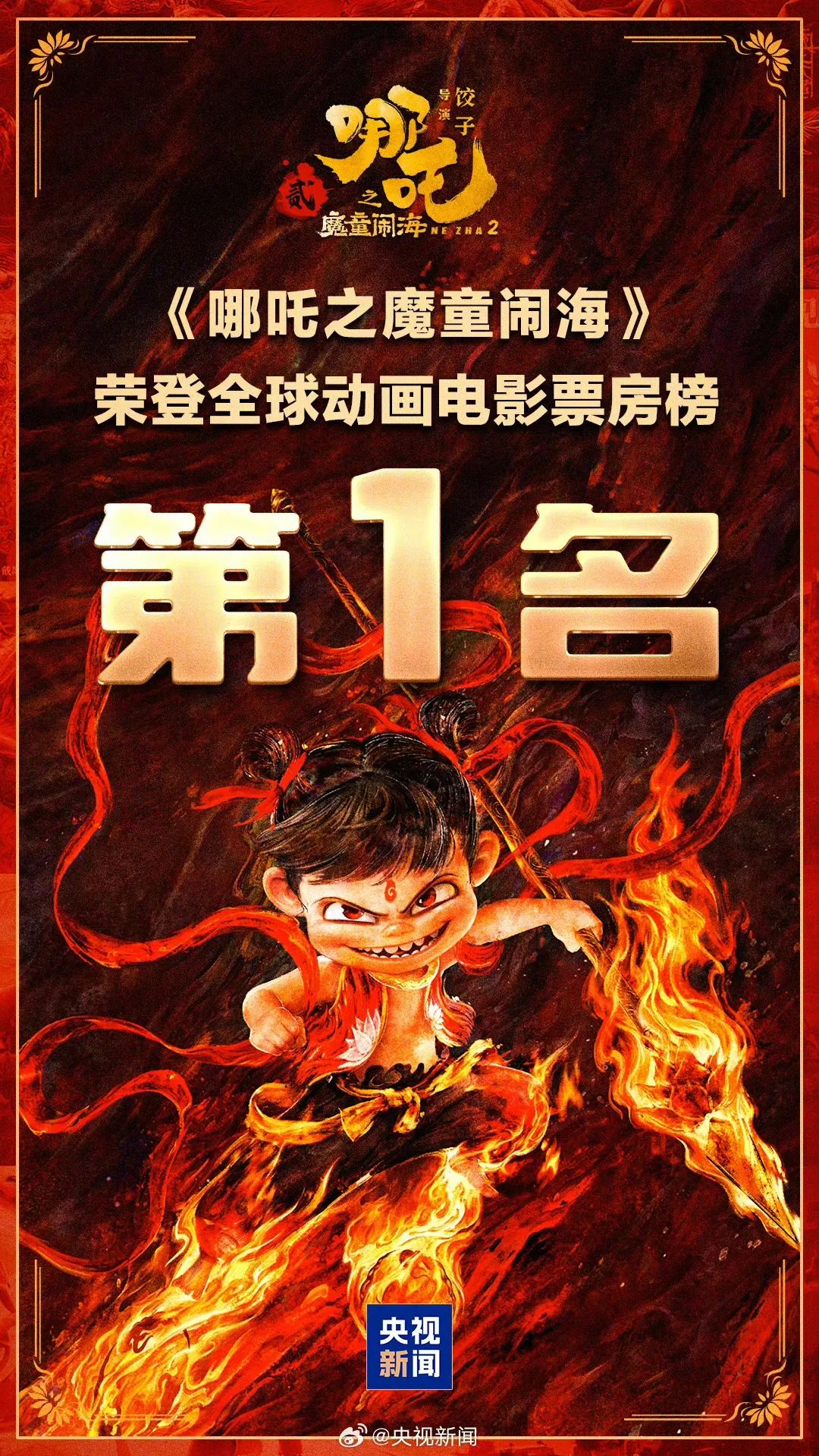

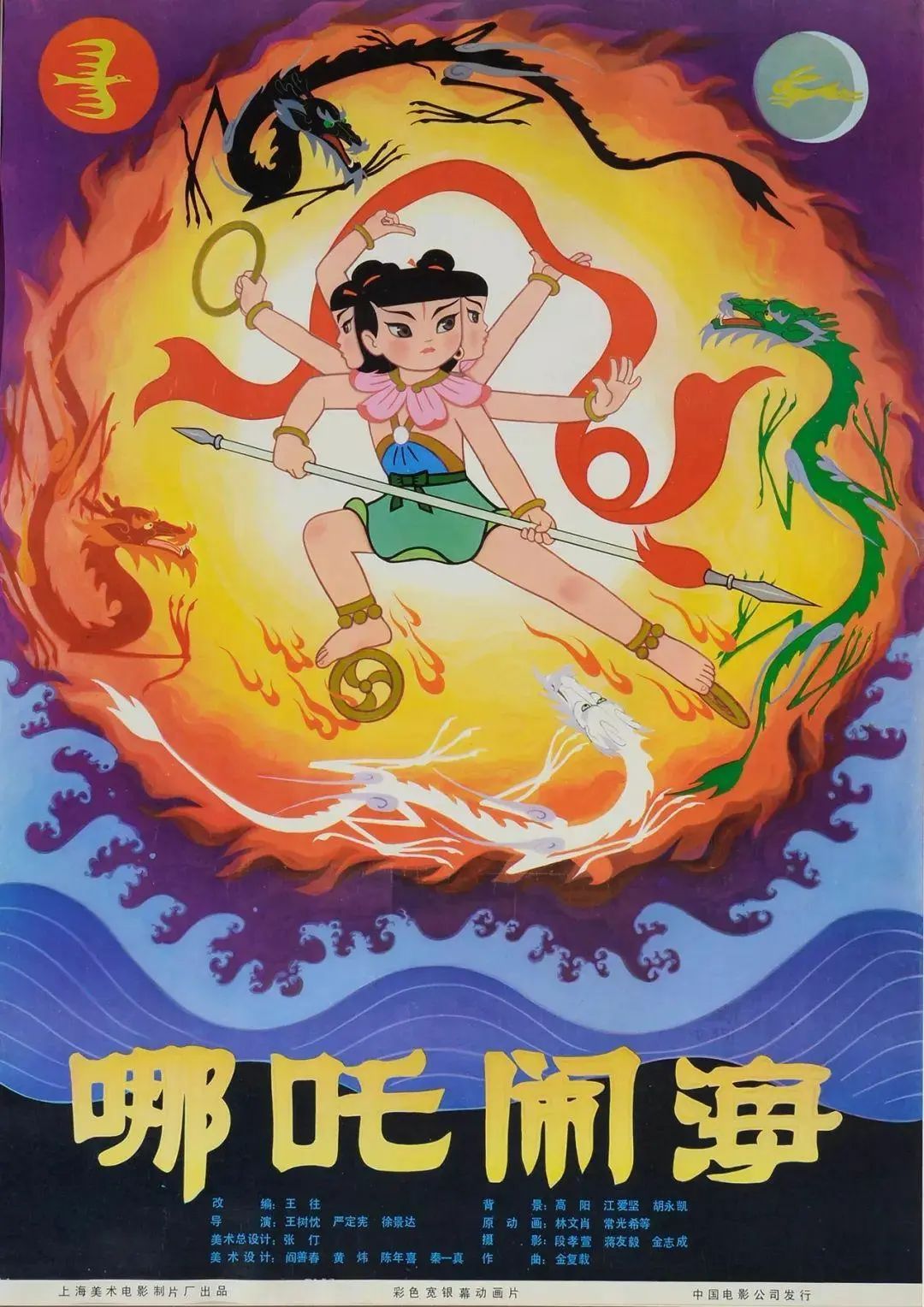

Director Jiaozi (of Nezha 2) credits the 1979 classic as his "spark of inspiration." While the new film reimagines Nezha as a defiant antihero, its core tension—"humanity versus divinity"—echoes the original’s duality. The 1979 Nezha, designed as both a vulnerable child and mythic warrior, navigated divine power and mortal limitations, cementing its status as a pinnacle of Chinese animation. Its recent resurgence, spurred by Nezha 2’s success, has even reignited screenings on platforms like Xinhua News Agency’s video channel.

The wechat video number of Xinhua News Agency broadcast the 1979 version of “NeZha Conquers the Dragon King”

In 1978, Zhang Ding—revolutionary artist, founding dean of the Central Academy of Arts & Design (now Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University), and chief art designer for “Ne Zha Conquers the Dragon King”—embarked on a two-month sprint to finalize character designs. Drawing from Dunhuang murals, Ming-era temple art, and folk woodblock prints, he fused decorative styles with bold colors (azure, emerald, crimson) to craft iconic figures: Ne Zha in his red bellyband, wielding cosmic ribbons; the arrogant White Dragon Prince; and earthy-toned generals. Zhang’s relentless revisions, including reshaping Ne Zha’s hair knot for dynamic animation, birthed a hero balancing innocence and divinity.

PART 02 From Screen to Mural: A Cross-Medium Cultural Symphony

In 1979, “Ne Zha Conquers the Dragon King” stunned Cannes as the first Chinese animation showcased at the festival, winning the Hundred Flowers Award for Best Art Film.

“NeZha Conquers the Dragon King”Poster

That same year, Zhang Ding transformed the film’s legacy into the monumental mural “Ne Zha Conquers the Dragon King” at Beijing Capital International Airport. Blending motifs from the animation, Chinese folk New Year paintings, and religious murals, the artwork depicted Ne Zha battling sea dragons king amid swirling waves—its lines echoing the grace of Tang-dynasty brushwork, colors channeling Dunhuang’s celestial palettes.

Zhang championed folk art as “the root of all visual creativity,” embedding it into academia and inspiring generations to mine cultural traditions. This mural, alongside the film, became twin pillars of China’s artistic identity—one dynamic, one static, yet both rooted in vernacular aesthetics.

Part of mural of "NeZha Conquers the Dragon King" by Zhang Ding

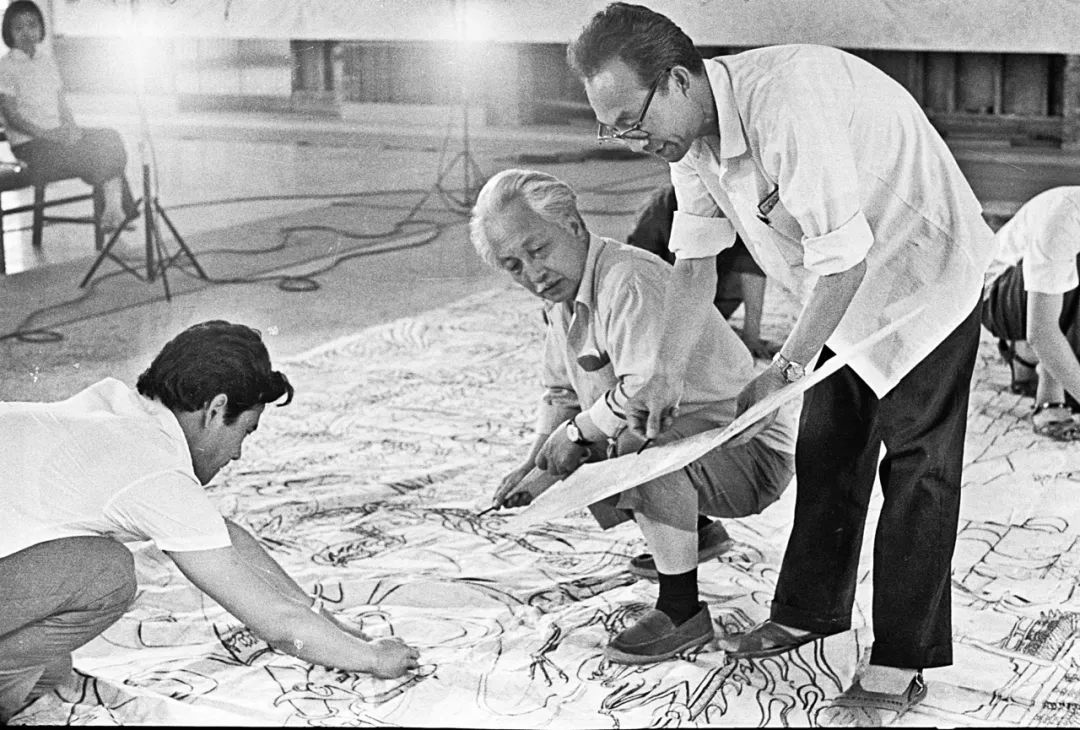

In the summer of 1979, Zhang Ding (middle), Zhang Yimin (left) and Chu Qien (right) painted the mural "Nezha Conquers the Dragon King" at Beijing Capital Airport, China

"Nezha Conquers the Dragon King" Mural

PART. 03 Havoc in Heaven: Zhang Guangyu’s Monkey King and the Birth of “Chinese School” of animation

Havoc in Heaven Design Drawing

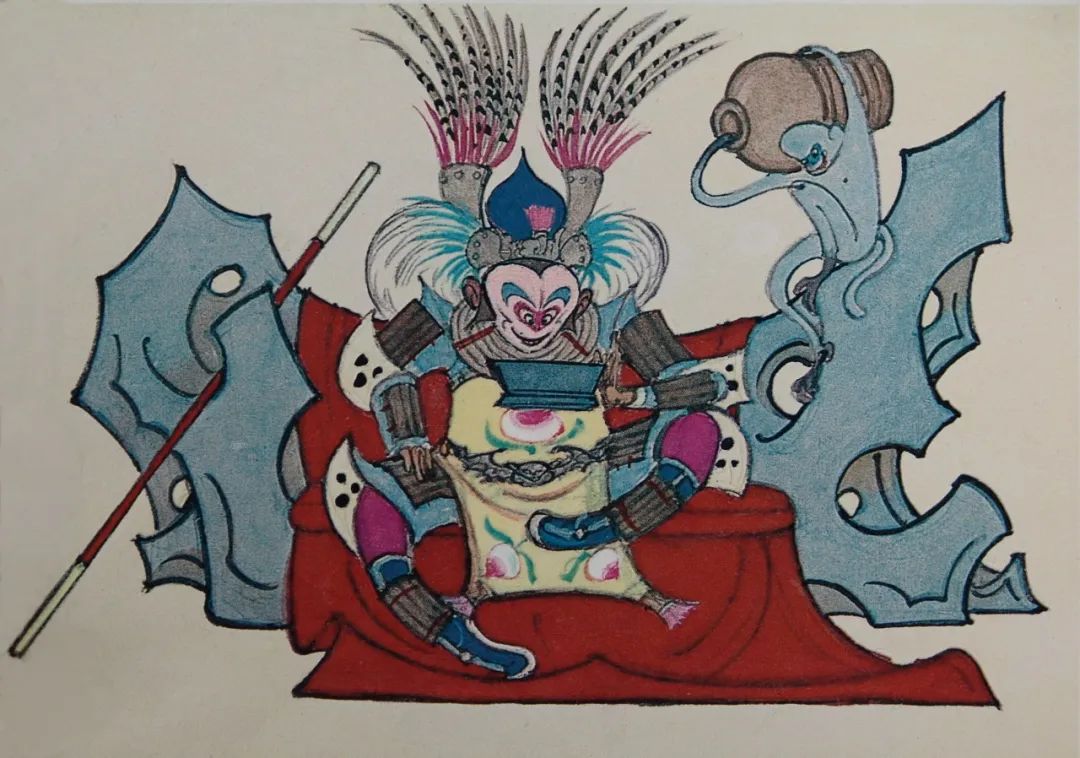

In 1960, Zhang Guangyu—renowned for his satirical comic “Journey to the West”—was tasked with designing characters for “Havoc in Heaven”. Merging Peking Opera masks, folk toys, and woodblock prints, he crafted a Sun Wukong (Monkey King) that fused human wit, simian agility, and divine might.

Havoc in Heaven Design Drawing

His design, praised by director Wan Laiming as "radiant and formidable," drew global acclaim, winning awards at Karlovy Vary and London film festivals.

Zhang’s work, refined from his 1940s comic Journey to the West, established a visual lexicon for Chinese animation. As Zhang wrote, "A character’s soul lies in their eyes, brows, and posture—lines and colors must breathe life into myth," a philosophy that birthed the “Chinese School” of animation.

"From Journey to the West

"From Journey to the West": A Satirical Chronicle to Animation Legend: Mr. Zhang Guangyu Mastered Folk Art’s ‘Seventy-Two Transformations’

PART 04Eternal Flame: A Century of Cultural Relay

From Havoc in Heaven to “Nezha 2”, China’s animation milestones are not solitary triumphs but a cultural baton passed across generations. As “Nezha 2”’s Wind Fire Wheels blaze across global screens, they carry forward the DNA of Zhang Guangyu’s ink-wash elegance and Zhang Ding’s folkloric rigor. Today’s animators, armed with digital tools and global sensibilities, reignite these timeless tales—proving that the aesthetic Long March begun in the 1960s is far from over.

The wheels of tradition, spun by time, will continue blazing across eras, forging Chinese animation’s next legends.

Planned & Edited: Xia Zhiwei

Sources: Official social media of Ne Zha II; CCTV News

Text Editors: Luo Xuehui, Xia Zhiwei, Wang Chenyue, Chen Jie

Reviewer: Wang Xiaoxin