【Editor’s Note】

From the decorative design for Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings” in celebration of the 10th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China to the innovative expansion of “Light Ink Painting”, from scaling new heights in artistic creation to deepening efforts in art education, He Baosen’s creative journey spans multiple disciplines. Throughout, he has consistently woven his personal artistic exploration into the broader tapestry of the nation’s cultural development.

Let us follow in the footsteps of Mr. He Baosen to uncover the stories behind his contributions to the decorative designs for the “Ten Great Buildings,” and to have a glimpse into the profound sense of duty and patriotic devotion that defined a generation of artists from the Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University (AADTHU).

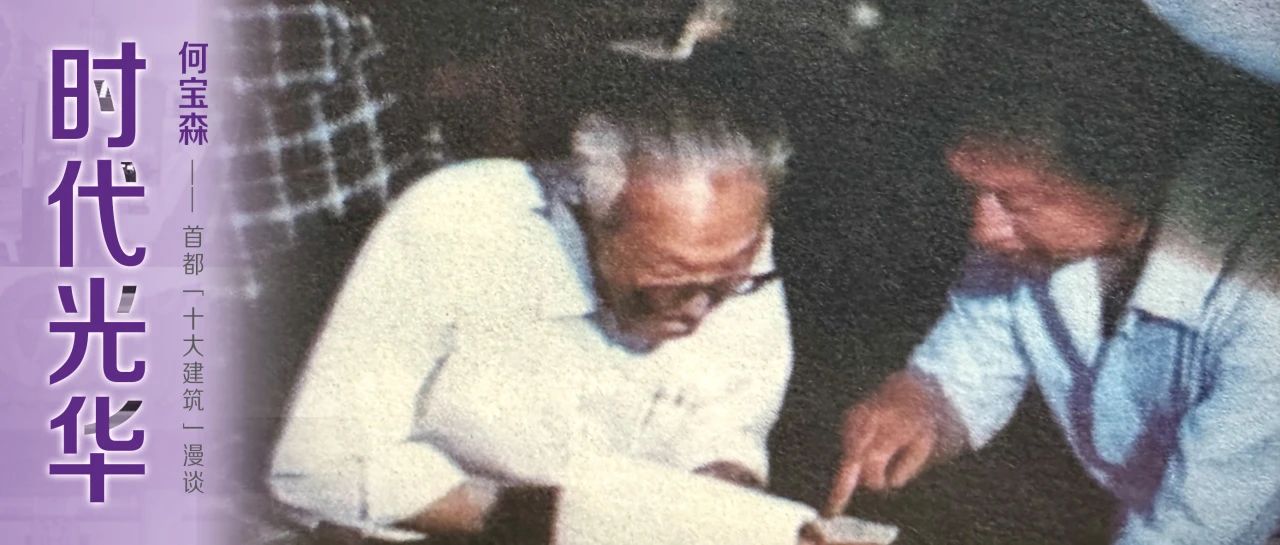

Splendor of the Times: Artistic Imprints in Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings”

An Exclusive Interview with He Baosen

He made significant contributions to the establishment and development of disciplines such as decorative sculpture, metal art engraving, and jewelry design at the Central Academy of Arts & Design (now the Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University).

As head of the Senior Professors Group at AADTHU, he mentored dozens of China’s renowned calligraphers and painters, including Su Shishu, a celebrated calligrapher.

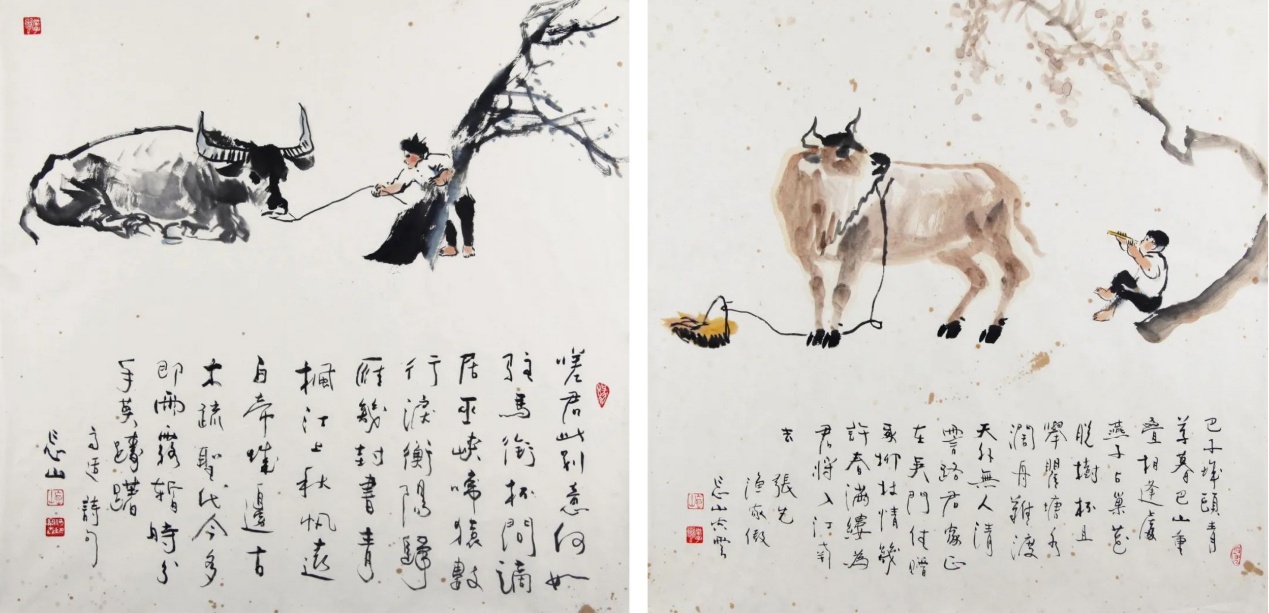

He is a pioneer of Chinese “light ink painting” which integrates the techniques of traditional Chinese ink wash painting with Western chiaroscuro methods, creating a style that embodies the charm of Chinese ink art alongside the aesthetic appeal of Western painting.

Mr. He Baosen is most often celebrated for his accomplishments in calligraphy, painting, and education. However, few are aware of his significant contribution as a student to the decorative design of Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings.” Many decorative elements of the National Museum of Chinese History and the National Museum of Chinese Revolution (which merged into the National Museum of China in 2003) bear witness to his wisdom and ingenuity.

On the interview scene

The Long March spirit in wild vegetable blossoms

In December 1938, He Baosen was born in Yunnan—a land of vibrant color, where emerald-green trees stand against rich red soil. His grandfather, a traditional literati, had a deep passion for collecting calligraphy and paintings. By the age of seven, he was already copying Qi Baishi’s “Gourd and Chicks” for study, a treasured piece in his grandfather’s collection, marking the beginning of his artistic enlightenment.

During elementary school, guided by his father, He Baosen knelt and bowed to become a disciple of Liao Xinxue, a Yunnan-based artist who had recently returned from studying in France. When he first witnessed Liao sketching under the crabapple trees at Kunming Normal College, the young He Baosen was deeply captivated by the vibrant colors of oil painting.

Paintings by He Baosen

The soil of his homeland nurtured not only vibrant and diverse landscapes, but also a soul yearning for artistic expression. In 1957, He Baosen was admitted to the Ceramics Department of the Central Academy of Arts & Design, where he studied under Mr. Zheng Ke. The following year, to meet the demands of the new era, the Academy decided to select outstanding students from various departments to establish new disciplines. Recognized for his talent, he was selected to join the newly created Ceramic Sculpture program.

He Baosen conducting teaching research with Mr. Zheng Ke

In August 1958, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China made the decision to construct the “Ten Great Buildings” in Beijing, including the National Museum of Chinese History and the National Museum of Chinese Revolution. Construction of these two museums began shortly thereafter.

Led by Jin Baosheng, a lecturer from the Central Academy of Arts & Design, He Baosen was assigned to the decorative design team for the two museums. Working alongside his instructors, he contributed to the sculpture and decorative elements of the exteriors, covering areas such as glazed tiles, column capitals, porch openwork carvings, colored flag carvings on the gates, and bronze reliefs.

“The main leader of this team was Zhang Kaiji, then chief architect of the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (BIAD). He patiently guided us on how to deeply explore the functional, historical, cultural, and symbolic significance of the architecture.” Even now, 67 years later, Mr. He Baosen, now in his advanced years, still feels immensely fortunate when reflecting on this valuable learning experience.

A group photo taken at the construction site of the National Museum of Chinese Revolution, featuring faculty and students from the Central Academy of Arts & Design and their counterparts from the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design during the second phase of artistic and decorative design work.

First row (from left): Li Mianlu, Zhang Youbang

Second row: Zhang Kaiji, Jin Baosheng, Luo Wuyi, Ji Siliang (Class of 1957, Ceramics Department), and others

Third row: Zhang Zhongkang (’56 Dyeing and Weaving), Li Xia, He Baosen (’57 Ceramics), and others

A graduation photo taken in front of the teaching building in July 1962, featuring faculty members Chen Shuliang, Zheng Ke, Zhu Danian, and Chen Ruoju with the Class of 1957. He Baosen is pictured third from the left in the back row.

While designing the openwork carvings for the porch, He Baosen immersed himself in revolutionary historical archives for inspiration. Ultimately, he found it in the wild vegetable blossoms that sustained Red Army soldiers throughout the Long March and skillfully conceptualized an openwork sculptural design. He meticulously studied the plants’ morphological characteristics, transforming them into dynamic sculptural patterns. Through the artistic rendering of every leaf and blossom, his final designs convey the iron will and indomitable spirit of the Chinese Communists and Red Army soldiers.

“These wild vegetables witnessed the hardships of the Long March, serving as a vital means of survival for the soldiers during their arduous journey. They symbolize their unyielding, resilient, and united spirit. My hope was to give tangible form to the Long March spirit, enabling people to see the weight of history and feel the hardships of the Long March through these sculptures,” recalled He Baosen. This creative concept was highly recognized and endorsed by Chief Architect Zhang Kaiji, which served as a tremendous encouragement to the young designer.

Artistic Interpretation of Patriotism

The ancient and solemn National Museum of China has always been a popular destination for visitors from China and abroad. Upon entering this cultural place, one would be immediately struck by the vibrant “colored flag carvings on the gates.” These flags stand in harmony with the Great Hall of the People, symbolizing the great victory of the Chinese revolution.

He Baosen still vividly recalls the design details of the flag carvings. “At the initial design stage, we drew inspiration from Soviet architectural styles while incorporating distinctive features of the People's Republic of China’s architecture,” he reflected. The design process was fraught with challenges. Originally, the team planned to use glazed tile firing techniques to create the entire colored flag sculpture. However, the limitations of glazing technology made it difficult to perfectly capture the original red hue of the flags. As a last resort, they turned to painting with oil-based pigments.

This compromise remains a lingering regret for Mr. He Baosen to this day.

He Baosen participated in the design of the “porch openwork carvings” and the “colored flag carvings on the gates” for the National Museum of Chinese Revolution.

In February 2003, the National Museum of Chinese History and the National Museum of Chinese Revolution were merged to form the National Museum of China (NMC). He reflected emotionally, “During the architectural renovation of the NMC, some of the designs I worked on were removed. Yet, it is some consolation that the front corridor was preserved, and the colored flag carvings on the main gate still stand tall.” He expressed deep pride in having contributed to a building of such national significance.

While working on this historic architectural project, he was only 20 years old, an age brimming with curiosity and dreams for the future. He recalled that during his time at the construction site, he had the privilege of briefly crossing paths with then-Premier Zhou Enlai. Premier Zhou once noted that these designs were not merely products of individual creativity; they embodied a profound connection to the national spirit and served as a tribute to the country’s history.

This brief encounter not only inspired He Baosen to persevere and carry forward his artistic path, but also strengthened his resolve to closely align his personal development with the national progress.

As timeless masterpieces, the decorative designs of “Ten Great Buildings” are admired for their ingenuity. The National Museum of Chinese History and the National Museum of Chinese Revolution are arranged in a courtyard layout in the shape of the Chinese character “目” (mù, meaning “eye”), creating a grand appearance with a relatively compact structure. The classically elegant Diaoyutai State Guesthouse comprises 17 reception buildings clad in blue bricks and red tiles. In a symbolic gesture reflecting the diplomatic principle of equality among nations regardless of size, the complex was deliberately designed without a “Building No. 1.” The multifunctional hall of Beijing Railway Station innovatively employed a “double-curved arch” architectural form.

Reflecting on the profound significance of the “Ten Great Buildings,” He Baosen emphasized that these structures are not only precious tangible cultural heritage, but also represent groundbreaking explorations in architectural structure and technology. Innovations such as thin-shell structures, prefabricated assemblies, and early applications of suspension systems marked important milestones in China’s architectural development, building upon the natural evolution of modern architectural concepts during the period of national economic recovery. These advances not only propelled architectural technology forward, but also demonstrated a meaningful dialogue between architectural artistry and historical memory. The “Ten Great Buildings” carry the spirit and collective memory of the nation, serving as enduring witnesses to the People’s Republic of China’s urbanization and prominent symbols of Chinese cultural confidence.

The New Long March: Setting Out Anew

With the passage of time, the “Ten Great Buildings” have become a cornerstone of Beijing’s urban landscape, laying the foundation for the city’s magnificent appearance today. As the symbol of both Beijing and the nation, their role in preserving heritage and inspiring innovation remains as vital as ever.

He pointed out that in-depth study of the “Ten Great Buildings” reveals the deep integration of Chinese architectural styles with international trends, forming a distinctive language of design with uniquely Chinese characteristics. The structures and decorative design of these buildings bear profound imprints of their time, serving as important manifestations of the nation’s cultural soft power.

He believes that while the “Ten Great Buildings” differ in style and form from modern iconic structures, they hold a unique historical and political significance, embodying the fervent aspirations of the people for the construction of the People’s Republic of China at the time. In contrast, contemporary architecture tends to prioritize functionality, market demands, and innovation in the design philosophy. Buildings from each era, therefore, reflect the distinct spirit and values of their time.

As a renowned painter, sculptor, and art educator in China, Mr. He Baosen’s works can be found across the country. His notable works include the Art of Painted Pottery mural in the Ziguang Pavilion of Zhongnanhai, the statue of Li Dazhao at the Li Dazhao Memorial Hall, the commemorative coin for the 100th anniversary of Chairman Mao’s birth, the mountain-carved statue of Laozi on Hainan Island, and the statue of Shennong (Yan Emperor) in Haitang Bay of Sanya. Each of these creations embodies his artistic conviction: “An outstanding art practitioner must possess both broad vision and profound cultural literacy.”

Mountain-Carved Statue of Laozi created by He Baosen

On the eve of the 2024 Spring Festival, he returned to his hometown in Qujing City, Yunnan Province, where he donated 53 pieces of calligraphy and painting. During an exchange session with art teachers from universities, primary, and secondary schools across Yunnan, he expressed his hope that students would have opportunities to appreciate original masterworks up close and experience firsthand the charm of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting. On the same occasion, the large-scale sculpture Long March—the Red Ribbon on Earth, designed and created jointly with his disciples, was officially unveiled.

Mr. He Baosen left a message for the younger generation: “Every era has its own Long March. I hope young people today will remember history, carry forward the fine traditions of the Chinese nation, and broaden their global vision. They should persist in integrating heritage with innovation, creating outstanding works that reflect both the spirit of our time and the soul of the Chinese nation, contributing artistic strength to the progress of human civilization.”

A group photo of faculty and students from the Class of 1978, Special Arts Department, taken in the winter of 1979.

Front row (from left): He Baosen, Quan Zhenghuan, Bai Zhen’ou, Li Deli.

Middle of the second row: Jiang Peiran.

A photo of the interview team and Mr. He Baosen

Special thanks to Guo Qiuhui and Zhang Jingsheng for their review of this article.

Produced by | Converged Media Center, Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University

Planning and Coordination | Chai Xinmeng

Interview | Chai Xinmeng

Copy Editing | Liu Feng

Written by | Jie Mingyue

Images Courtesy of | He Baosen, Zhang Jingsheng

Video | Peng Haopeng

Graphics Editing | Chen Jie, Luo Xuehui

Reviewed by | Wang Xiaoxin