Splendor of the Times: Artistic Imprints in Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings”

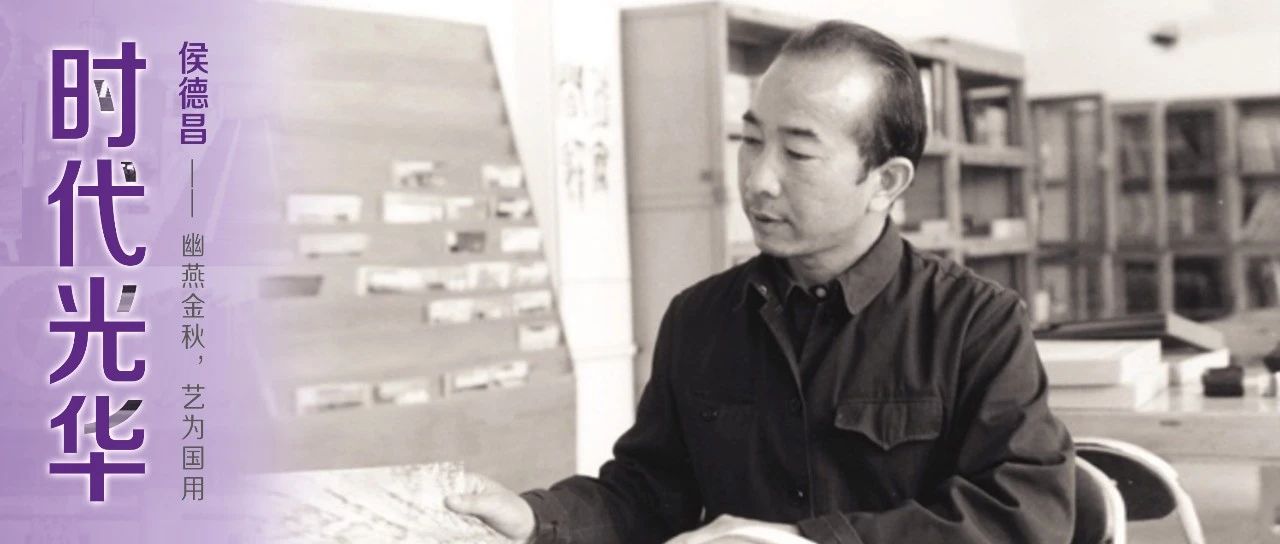

An Exclusive Interview with Hou Dechang

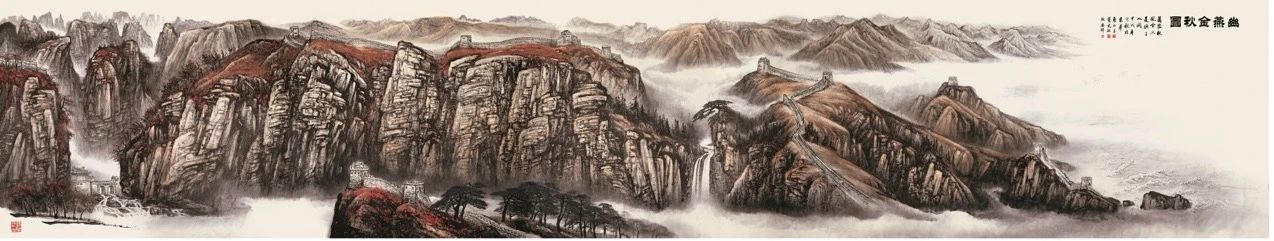

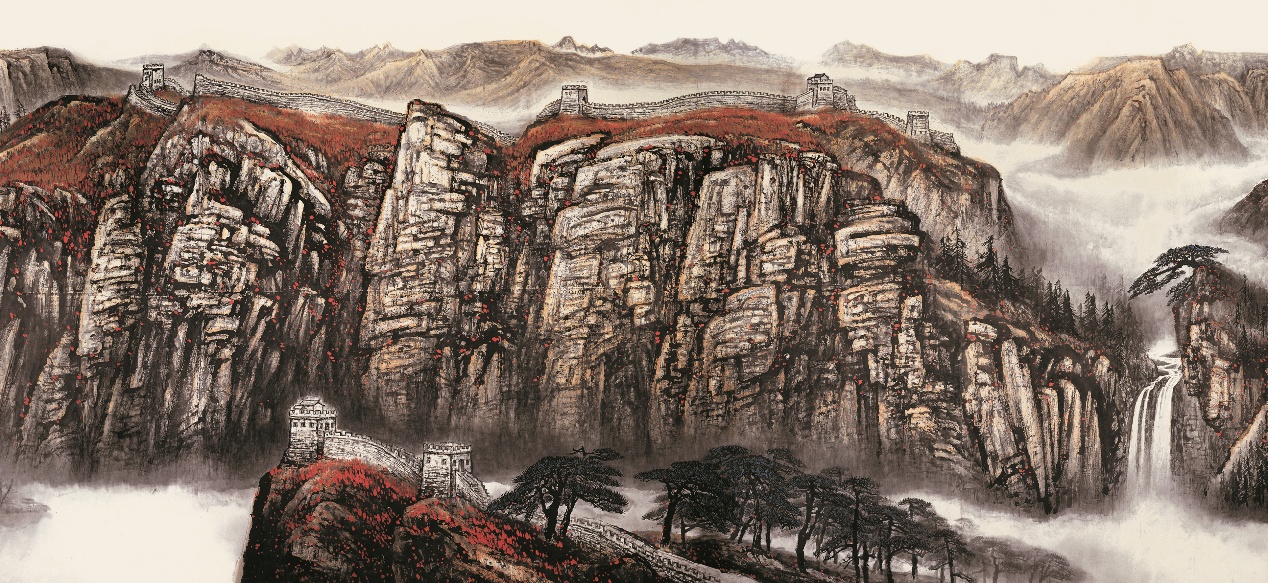

Amidst rugged peaks and towering pine trees, the monumental traditional Chinese painting Golden Autumn in the Northland vividly depicts the majestic autumn scenery stretching from Laolongtou in Beidaihe, Hebei Province, to the Juyongguan Great Wall. Not only is it the largest traditional painting hanging in the Great Hall of the People, one of Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings”, but it has also become an iconic work in the history of modern Chinese art. For three decades, it has made near-daily appearance on China Central Television’s flagship news program “Xinwen Lianbo,” earning the distinction of being “the most frequently televised landscape painting in China.”

The principal artist behind this masterpiece, Professor Hou Dechang with the former Central Academy of Arts & Design (now the Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, or AADTHU), began engaged in the decorative design of the Great Hall of the People as early as his student years.

The Great Hall of the People embodies China’s national image and spirit. It has witnessed countless historic moments and bears the creative dedication and wisdom of generations of artists. With his profound artistic vision and cultural literacy, Hou Dechang played a significant role in the Hall’s construction and decoration. From designing blue-and-white porcelain to creating the monumental traditional Chinese painting Golden Autumn in the Northern Land, his artistic journey is deeply intertwined with the story of the Great Hall of the People. His works not only exemplify the charm of traditional Chinese art but have also become an integral part of the nation’s image.

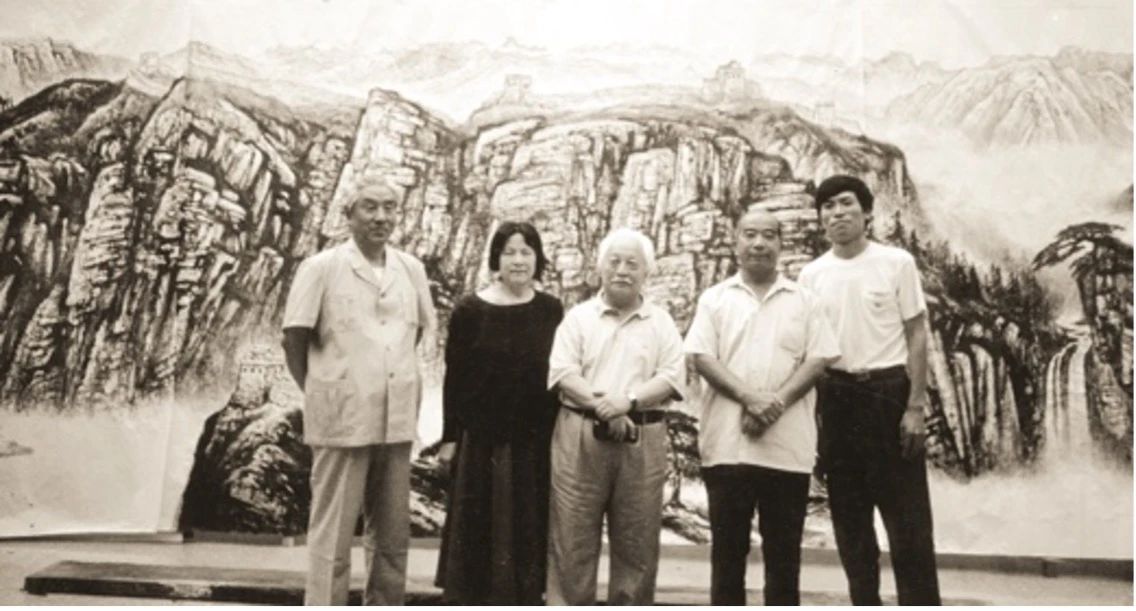

An exclusive interview with Mr. Hou Dechang (center)

Emerging Talent: The Origin of the Blue-and-White Porcelain in the Great Hall of the People

In December 1933, Hou Dechang was born into an ordinary farming family in Henan Province. Little did anyone expect that 43 years later, his clerical script calligraphy would stand out among numerous submissions and be prominently displayed in the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall. And 60 years later, a monumental painting created under his leadership would become one of the most iconic artistic features in the Great Hall of the People.

From a young age, Hou showed a keen interest in calligraphy and painting. Once, a neighbor gave him a yellowed, slightly curled copy of a calligraphy book by Yan Zhenqing (a renowned calligrapher in the Tang Dynasty), a treasure he cherished dearly. Amidst chores like cutting grass and gathering firewood, he would still find moments to practice. During festivals, he would listen to storytellers, attend temple fairs, visit lantern festivals, and admire New Year paintings… These experiences with folk art laid a solid foundation for his artistic awakening. Despite extremely challenging conditions, he balanced farm work with self-study, persistently pursuing knowledge and creative growth.

A group photo of faculty members Quan Zhenghuan (front row, second from right) and Zhang Shouzhi (front row, fourth from right) with the Class of 1956 from the Ceramics Department in front of a building on the Baiduizi campus in the winter of 1956 (Hou Dechang is pictured fourth from the right in the second row)

At the age of 22, Hou was admitted to the Department of Ceramic Art at the Central Academy of Arts & Design, marking the formal beginning of his artistic journey. In 1958, preparations unfolded for Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings”. “I was in my third year at the Academy,” he recalled. “Under the guidance of Mr. Mei Jianying, a pioneer of the People's Republic of China’s ceramic art, our team was stationed at the Beijing Hotel. We were tasked to design the first batch of blue-and-white porcelain for the Great Hall of the People. We worked there during the day and slept on the carpet at night.” Now 92 years old, Hou still remembers that time with striking clarity.

The meticulous process and extensive discussions over the design of the inaugural blue-and-white porcelain were later documented by Mr. Mei Jianying in an article titled Design of Blue-and-White Porcelain, published in April 1959 in Decoration—then the nation’s only comprehensive academic journal dedicated to arts and crafts. In the article, Mr. Mei wrote: “To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the People's Republic of China, faculty and students from the Ceramics Department of the Central Academy of Arts & Design took part in designing blue-and-white tableware and tea sets for the state banquet hall of the Great Hall of the People. The design was required to be simple yet elegant, dignified yet clear, and convey a grandeur befitting our nation’s great spirit. The task was particularly challenging given that some of the participating students had not yet received formal training in blue-and-white design.”

A group photo taken in the winter of 1958 in front of the Beijing Hotel, featuring Mei Jianying (front row, third from left), head of the Ceramics Department, with students from the Class of 1955 and 1956—including Hou Dechang (second from right)—during their work on designing tableware and tea sets for the Great Hall of the People.

Professor Lü Xiaozhuang from the Ceramics Department, now in her nineties, recalls that the blue-and-white porcelain designs for the banquet hall of the Great Hall of the People was created under the guidance of Department Head Mei Jianying and Teaching Assistant Zhang Shouzhi, together with students from the Classes of 1955 and 1956. The design process followed a multi-step approach involving reporting, discussion, site visits, and selection, integrating the project with student education and comprehensive skills development. The final decorative pattern was based on a proposal by Hu Meisheng, a student from the Class of 1956. Subsequently, Zhang Shouzhi and Lü Xiaozhuang led the students to the Jingdezhen porcelain district to oversee production.

Professor Hou recalls that during this period, he and his classmates balanced academic studies with design work. As class monitor, he was often asked by Mr. Mei Jianying to visit restaurants to study the features of Chinese cuisine, observe how tableware was used in practice, and gather feedback from chefs on proposed designs. This experience marked his first hands-on design practice at the Academy.

The design requirements emphasized distinct national characteristics, an elegant and dignified style, harmony with the architectural environment, and the importance of being economical, aesthetically pleasing, and functional. To ensure the project’s success, the design team held numerous seminars to discuss and refine proposals. Special symposiums were organized where every participant’s input was recorded, a process that proved highly enriching for all involved.

For instance, the designs had to align with the building’s overall decorative theme to achieve visual coherence, while also taking into account manufacturability and practical use. The goal was to create tableware that was not only beautiful but also economical and efficient to produce. Through collective brainstorming and mutual learning between instructors and students, the aesthetic ideal of “dignity and clarity” was instilled into the ceremonial vessels. This practice, which transcended the boundaries of classroom and factory, not only produced iconic porcelain that blends functional beauty with symbolic significance, but also vividly illustrated, at a turning point between tradition and modernity, the enduring idea that “only what is truly national can become universal.”

A group photo of faculty and students from the Ceramics Department of the Central Academy of Arts & Design with Li Shuming (fifth from left), Deputy Secretary of the Academy’s Deputy Party Secretary, and Mei Jianying (fifth from right), Head of the Department on New Year’s Day, 1959. Hou Dechang is in the back row, fifth from the right.

Hou Dechang’s journey from the rural land to the national artistic stage coincides with the rise of The People's Republic of China’s arts and crafts within its broader national narrative. In 1958, as the Beijing’s “Ten Great Buildings” project rose to the call of the era, this farmer’s son assumed a pivotal role, where the aesthetic sensibilities shaped by Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy and vibrant folk traditions converged with Professor Mei Jianying’s design philosophy of “national grandeur. In this convergence of tradition and modernity, blue-and-white porcelain was reborn, glowing with renewed brilliance.

Magnificent Landscapes: The Creation and Legacy of Golden Autumn in the Northland

Upon graduating in 1961, Hou was invited to teach at the academy due to his outstanding academic performance. While dedicated to his role in the ceramics department, he also cultivated profound expertise in calligraphy and painting.

The Ceramics Department’s Class of 1956 with instructor Lü Xiaozhuang (fifth from left) on campus, 1961. Hou Dechang is third from the left.

The Ceramics Department’s Class of 1956 at the National Agricultural Exhibition Center in the summer of 1961. Hou Dechang is first on the right.

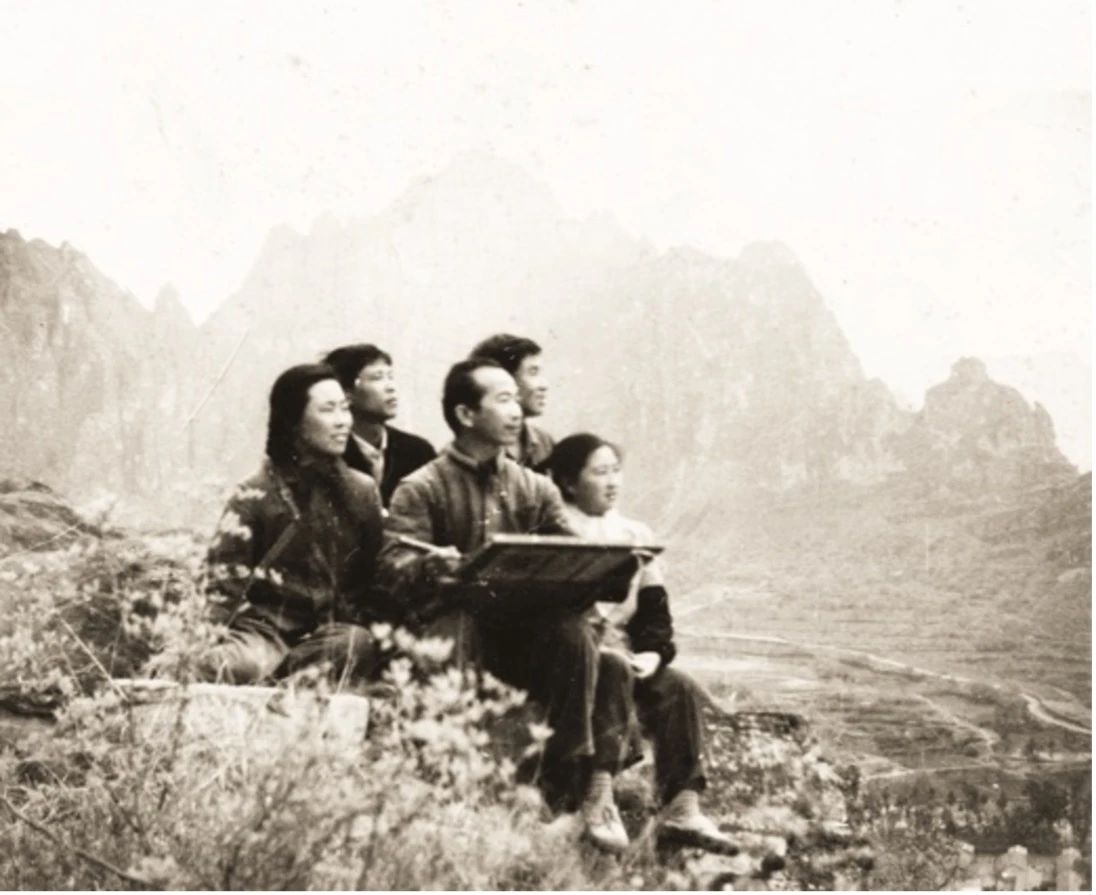

Hou Dechang (center, holding a sketchbook) leads a plein-air painting session for students at Shidu in the spring of 1966.

In 1994, thirty-five years after its completion, the Great Hall of the People needed a comprehensive renovation of its interior decorations, pipelines, and electrical systems. As a key venue for major diplomatic events and important state conferences, the East Hall was a part of this upgrade.

Previously, Hou had been commissioned to create a 110-meter-long landscape painting titled Soul of China, which was unveiled at a press conference in the Great Hall of the People. His work on this piece so impressed Chen Baoshan, the official in charge of the building’s artistic decoration, that he approached Hou with another major commission.

“Chen Baoshan was aware of my apprenticeship under Mr. Zhang Ding,” Hou recalled. “His original idea was for Mr. Zhang and me to collaborate on a large-scale painting themed on the Great Wall.” Hou added that due to the tight deadline, they began gathering material at Huangyaguan Pass while simultaneously drafting the composition. The work was carried out at the Beiyuan Guesthouse, with a completion window of just one week. To meet this demanding schedule, Hou immediately summoned two of his former students from Henan, Geng Anhui and Dou Xianmin, to join the urgent creation process in Beijing.

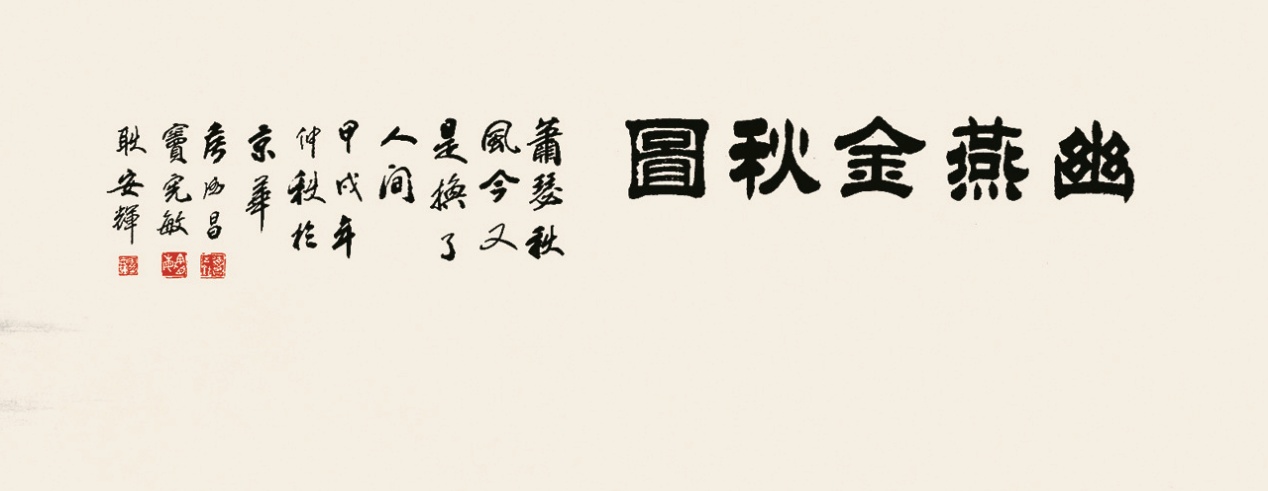

Within three days, Mr. Zhang Ding completed a preliminary sketch in ink, while Hou Dechang worked day and night to produce the full-color draft. The original work, initially titled A Panorama of the Land, was credited to Zhang Ding, Hou Dechang, Dou Xianmin, and Geng Anhui. It was Mr. Zhang who later proposed changing the title to Golden Autumn in the Northland and adding the lines from Chairman Mao’s poetry:

“Today the autumn wind still sighs, But the world has changed!”

Once the draft was approved, the team began working around the clock to complete the monumental painting. Hou recalled: “Perhaps out of a sense of duty, or simply carried away by emotion, I summoned the courage to wield the brush with abandon across the vast canvas—16 meters long and 3 meters high. Using a 3-centimeter-wide brush, I textured massive, rugged mountains and rocks with forceful strokes.”

When fellow painters later marveled at his audacious technique, he replied simply: “It was pure passion that guided my hand.”

A photo taken in 1994 at the painting site of Golden Autumn in the Northland in the East Hall of the Great Hall of the People, featuring (from left to right): Chen Baoshan, Zhang Ding’s wife Li Zhao, Zhang Ding, Hou Dechang, and Geng Anhui.

“Throughout the creative process, Mr. Zhang Ding provided guidance at every stage. As the work neared completion, he came to the site in person to offer his suggestions. Although the initial draft credited him as a co-author, he insisted on removing his name from the final version, stating that he had not applied a single brushstroke himself.” Recounting this story behind the credits, Hou Dechang remains deeply moved.

The installation of the monumental painting also presented challenges. With the East Hall undergoing renovation at the time, the mounting and framing of the piece had to be carried out on the floor. This meant hoisting the exquisitely crafted hardwood frame that weighed over a ton and securing it onto light-gauge steel studs. On September 25, 1994, more than 40 workers from the decoration company, assisted by three cranes operating a pulley system, worked in coordination for four hours to successfully install the giant artwork onto the wall.

Prior to National Day in 1994, Hou Dechang was commissioned to create the large-scale traditional Chinese painting Golden Autumn in the Northland (300 × 1600 cm) for the East Hall of the Great Hall of the People.

Art in Service of the Nation: A Life Devoted to Art

To this day, Golden Autumn in the Northland remains prominently displayed in the East Hall of the Great Hall of the People, bearing witness to countless historic moments in China’s modern history.

A section of the painting Golden Autumn in the Northland

In creating this monumental work, Hou blended the techniques of ink wash and splash ink, weaving traditional landscape aesthetics together with modern national symbolism. From gathering inspiration at Huangyaguan Pass to wielding the brush at Beiyuan Guesthouse, from Mr. Zhang Ding’s humble decision to withdraw from credit to the coordinated effort of over 40 workers hoisting the giant painting into place, this artistic relay not only produced a historic gift to the nation, but also embodied the ideal of “art in service of the nation.” Hou noted that the Great Hall of the People is a symbol of the Chinese nation and a place cherished by all its people. Having had the honor of participating in its decoration, he regards it as one of the highest privileges of his artistic life.

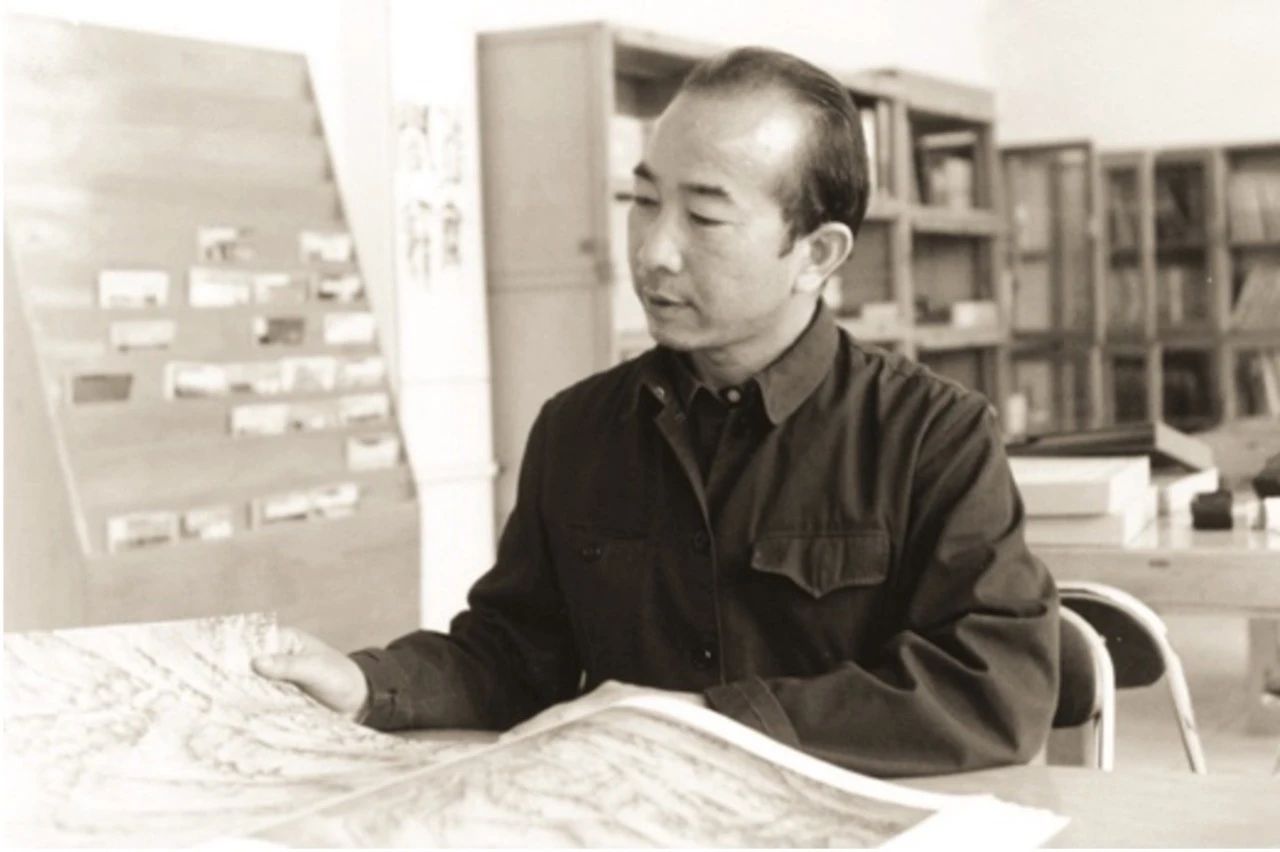

Hou Dechang reviewing art albums in the academy library in the 1980s

Calligraphy by Hou Dechang, created for the documentary commemorating the Academy’s 35th anniversary in 1991

The artistic accomplishments of Hou Dechang are manifest not just in his paintings and designs, but also in his creative philosophy that forges a powerful link between art and national spirit. His distinguished career stands as a vivid embodiment of the fusion between modern Chinese art and the nation’s cultural narrative. Today, his oeuvre continues to inspire succeeding generations of art students and creators to offer their own wisdom and strength to the enrichment of the nation’s cultural landscape.

Hou Dechang demonstrating traditional Chinese painting techniques during a class in 1991

Professor Zhang Jingsheng and student journalists interview Mr. Hou Dechang

From designing blue-and-white porcelain imbued with national spirit for the Great Hall of the People, to capturing the ethos of an era through the imagery of the Great Wall in Golden Autumn in the Northland, Hou Dechang has demonstrated through his practice that a true artist must be both an interpreter of the nation’s spirit and a shaper of its epochal character.

Special thanks to Guo Qiuhui and Zhang Jingsheng for their review of this article.

Produced by | Converged Media Center, Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University

Planning and Coordination | Chai Xinmeng

Interview Coordination | Zhang Jingsheng

Interview & Copy Editing | Chai Xinmeng, Miao Yize

Written by | Jie Mingyue

Images Courtesy of | Hou Aijing, Zhang Jingsheng

Video by | Chen Jiayan

Graphics Editing | Chen Jie, Luo Xuehui

Reviewed by | Wang Xiaoxin